I had a great conversation with my Year 10 set when doing geometric reasoning a couple of weeks ago – they’d done it all before, so we whizzed all the shape and angle properties in about twenty minutes, but I constructed one from the other, much as Euclid built up his ideas in the Elements. Because they’re a top set and I like upsetting/challenging them, when one of them said “angles in a triangle ALWAYS add up to 180 degrees”, I decided that I’d tell them they were wrong.

It’s curious that when we make statements to pupils like “angles in a triangle add up to 180”, we never think to caveat that with “on a flat surface”, possibly because all of secondary school mathematics (bar some A Level) goes on in flat exercise books and all the triangles we consider are not curved.

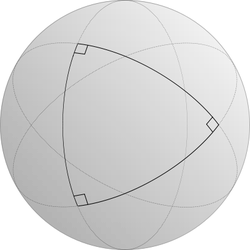

Draw a triangle on a spherical surface, and you end up with an angle sum greater than 180 degrees. The best example of this is the Earth, which approximates a sphere well enough – imagine starting at the North pole and following two separate longitude lines down to the Equator to form a triangle. As both of the longitude lines meet the Equator at 90 degrees, the total angle sum must be greater than 180 degrees. This idea obviously has one very real and important application: navigation, including modern GPS services.

Surely if there’s a surface with positive curvature (spherical, with angle sum greater than 180) and zero curvature (flat, with angle sum exactly 180), there’s also one with negative curvature. That’s hyperbolic space, and I can’t pretend I still remember all the important things about it from my degree studies. One analogy I do like, however, is that from Alex’s Adventures in Numberland – the saddle bit in the middle of a Pringle gives a perfect representation of a (local) hyperbolic space (Bellos makes it clear that we need to disregard the edge bits). This (unverified) source even gives the equation of a “Pringle-space”.

There’s even a tenuous link to yesterday’s post too, in that I’m going to mention another female mathematician, Daina Taimina, and another crafty maths project, namely hyperbolic crocheting – feeling that the Pringle analogy was insufficient, she decided to crochet models of hyperbolic planes to use in her teaching. It’s worth having a look at some of the models – they’re fascinating. Unfortunately, they don’t translate well to knitting, and I just do not crochet.

Image credits

”Crochet hyperbolic kelp” by Margaret Wertheim. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

“Triangle trirectangle” by Coyau / Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

“Pringles Chip” by Quant – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.