Bit of a random topic for my third SBPC, but bear with me. Over the weekend, my fiance dragged me to watch Jurassic World; I wasn’t keen, as I missed the Jurassic Park hype when I was younger, and don’t really enjoy action films. Since watching Jurassic World, we went back and watched three episodes of Planet Dinosaur – I’d never seen it before and found it fascinating, although the CGI looks a little dated now!

While we were watching it, we ended up discussing the huge time frames involved in the evolution of both dinosaurs and life in general. When I visualise dinosaurs, I imagine all the famous ones like Tyrannosaurus Rex, Stegasaurus and Diplodocus all roaming the planet at the same time. Something that struck me was the phenomenal length of time that dinosaurs in general were on the planet, and the (relative) shortness of the time that each recognisable species was around.

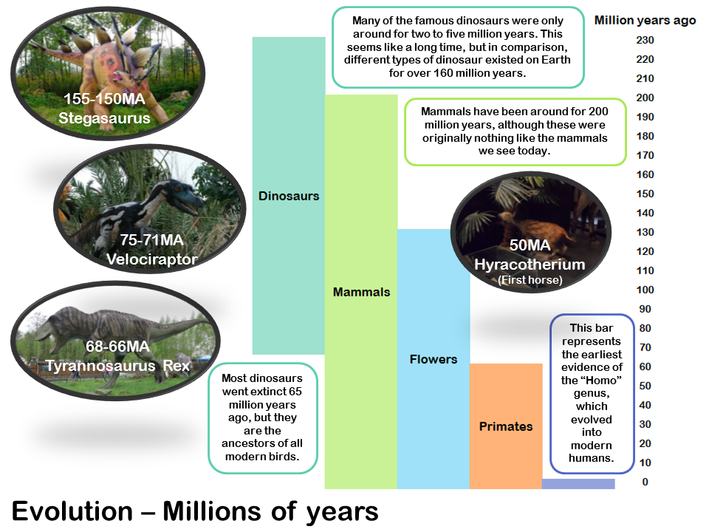

This got me thinking about how we struggle to think about really large numbers. I did a bit of research last night, and discovered that the Earth is about 4.5 billion years old (with a 1% tolerance, which works out at about 500 million years error – I’m sure there’s a lesson about error margins there somewhere), whereas dinosaurs went mostly extinct 65 million years ago, and the first humans appeared about 1 million years ago. In my mind, that’s all just “a really long time ago” – it’s difficult to get a handle on the difference between 4.5 billion and 65 million.

When I taught logarithms to my sixth formers a couple of years ago, I was reading Alex’s Adventures in Numberland at the time. In the first chapter, he talks about evidence that shows that humans naturally think logarithmically rather than in a linear fashion. We discussed this in the lesson and decided that it’s probably true – here’s the quote that summed it up best for me:

Our understanding of the passage of time tends to be logarithmic. We often feel that time passes faster the older we get. Yet it works in the other direction too: yesterday seems a lot longer than the whole of last week.

Some of the other evidence and discussion in that chapter of the book is fascinating, particularly discussions about early number development and the experiments done with chimpazees – it’s well worth reading if you’ve not done so already.

It seemed that this kind of thinking was at play with my visualisation of the evolutionary story of the Earth – my lifetime is a drop in the ocean of human evolution, which in turn is practically insignificant in the lifespan of our planet (dating from first recorded history, just over 0.0001%).

I had a bit of a play this morning, and made that poster/picture showing evolution in millions of years. I’m not entirely sure what I’m going to do with it – I’m planning another few, one looking at billions of years, one looking at thousands of years, and possibly one looking at technological advancements over the last hundred years.

I feel like there might be some nice connections to standard form and place value here – I don’t think I’d plan a lesson around this concept, but it might work nicely for a ten-minute discussion.

I’ll post links to all the posters when I’m done – let me know if you’ve got any brain waves for developing this in the classroom!